Mediterranean Fibre Cable Cut - a RIPE NCC Analysis

Analysis by the RIPE NCC Science Group with contributions from Roma Tre University.

Editors: Rene Wilhelm, Chris Buckridge

Introduction

On the morning of 30 January 2008, two submarine cables in the Mediterranean Sea were damaged near Alexandria, Egypt. The media reported significant disruptions of Internet and phone traffic in the Middle East and South Asia. About two days later, a third cable was cut, this time in the Persian Gulf, 56 kilometers off the coast of Dubai. In the days that followed more news on other cable outages came in.

The RIPE NCC Science Group has looked at the impact these events had on Internet connectivity by analysing data collected by RIPE NCC Information Services.

About Submarine Cables

the history of submarine telecommunications cables goes back to 1850 when the first international telegraph link between England and France was established. Eight years later the first trans-Atlantic telegraph cable linked Europe to North America.

In the 20th century telephony became the driving force for submarine cable deployments. TAT-1, the first trans-Atlantic telephone cable, was installed in 1956; it had the capacity to transmit 36 analog phone channels simultaneously. These days fibre-optic submarine cables carry the bulk of the trans-oceanic voice and data traffic. Maximum capacity is now in the order of 1 Tb/s, equivalent to 15 million old analog phone calls. Compared to satellites, submarine cables offer higher capacity and, because of the shorter distance, feature much better latencies. Cable systems are also more cost effective on major routes.

In the past two decades many of these cables have been deployed, primarily triggered by the explosive growth in Internet traffic.

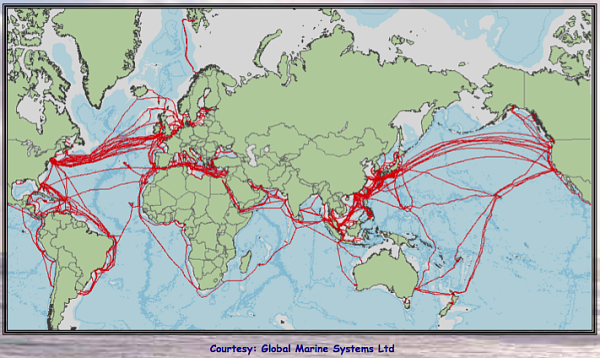

World map of submarine cable systems

The world map of cable routes shows that Europe, North America and East Asia are well connected; numerous cables connect the continents and countries. However, Africa, the Middle East and South Asia have far fewer cable systems. Looking at the available bandwidth or capacity in these cables [1], the differences become even more apparent. Faults in cables connecting these regions therefore have a higher impact than comparable faults in trans-Atlantic cables.

Although they rarely make news headlines, cable faults are not uncommon. Global Marine Systems, a company active in submarine cable installations and repairs, reported more than 50 failures in the Atlantic alone in 2007 [2]. A study [3] on behalf of the Submarine Cable Improvement Group shows 75% of all faults are caused by external aggression (physical damage). Of these, three out of four were attributable to human activities such as fishing, anchors and dredging. Natural hazards such submarine earthquakes, density currents and extreme weather were responsible for the remainder.

To limit the impact of such faults, cable systems often have build-in redundancy. Ring structures, for example, cross the ocean twice, each cable segment taking a geographically different route. When one segment breaks, signals can still reach the destination over the other segment(s). Repairs can then take place without much media attention.

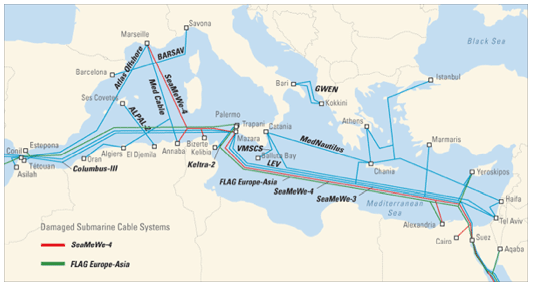

Location of the Mediterranean Cables

image source: Telegeography

The International Cable Protection Committee provides lists of deployed cable systems on their website [4]. Several smaller cables connect most regions bordering the Mediterranean. Spain, Morocco, France, Algeria, Italy, Tunisia, Greece, Libya, Cyprus, and Israel have multiple connections. However, only three cables connect Europe to Egypt, the Middle East and Asia: Flag Europe Asia, SEA-ME-WE4 and its predecessor SEA-ME-WE3. When the first two failed on 30 January 2008, the low capacity SEA-ME-WE3 was left as the only cable system providing a direct route from Europe to the region. All other options for rerouting traffic involved much longer cable routes or satellite systems.

Event Timeline

The following events are known/confirmed:

- Wednesday, 23 January 2008 (exact time unknown):

FALCON cable, segment 7b damaged (Persian Gulf)

Note: This is one week prior to the Mediterranean outrages. - Wednesday, 30 January 2008, 04:30 (UTC):

SEA-ME-WE-4 cable, segment 4/Alexandria-Marseilles, 25 kilometers from Alexandria, Egypt. - Wednesday, 30 January 2008, 08:00 (UTC):

FLAG Europe-Asia cable (FEA), segment D (EG-IT) cut approximately 8.3 kilometers from Alexandria, Egypt - Friday, 1 February 2008, 05:59 (UTC):

FALCON cable, segments 2 and 7a (AE-OM) cut approximately 56 kilometers from Dubai, UAE - Friday, 1 February 2008 (exact time unknown):

Unidentified cable, between Halul (QA) and Das (UAE) - Friday, 8 February 2008 (exact time unknown):

SEA-ME-WE-4 repair completed - Saturday, 9 February 2008, 18:00 (UTC):

FEA segment D repair completed - Sunday, 10 February 2008, 10:00 (UTC):

FALCON cable repair completed - Thursday, 14 February 2008:

Doha-Halul part of the unidentified QA-UAE cable "to be operational soon"

Note: Date and time for FEA segment D and FALCON segments 2 and 7a cable outages were reported by FLAG Telecom on their website. Other dates are from news reports. The SEA-ME-WE4 operators have not published exact times of cable failure and repairs. The timestamps for SEA-ME-WE4 failure are from clear observations in measurement data (both BGP monitoring and active measurements).

Effects of a Cable Cut

When a communications cable system used for IP connectivity fails, two things can happen:

- Networks become unreachable, meaning they disappear from the Internet; or

- Traffic is rerouted

Every individual IP link set up over the failed cable will be subject to one of these two options. Both options, however, can refer to a number of specific scenarios:

- Networks may become unreachable because no action is taken, meaning packets fall in a "black hole"

- Networks may become unreachable because the (only) upstream provider withdraws route announcements

- Traffic may be rerouted on the IP level, either by manual reconfiguration or by routing protocols like BGP reacting to a loss of IP connectivity to previously preferred routers

- Traffic may be rerouted on the data link layer. The (virtual) circuits on which an IP link has been set up are changed to follow a different physical path.

In the analysis below we see evidence that all of the above occurred after the outages on the two Mediterranean cables. The outages on the FALCON cable are not visible in our data. If the FALCON cable failures had significant effects on Internet connectivity, these were obscured in our data by the network outages, the network congestion and the rerouting activities triggered by the problems in the Mediterranean.